Visiting Deborah Butterfield’s Horses

“Essence: The Horses of Deborah Butterfield” is a new equine art exhibition at Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

by Karen Braschayko

Appealing to horse enthusiasts, to lovers of sculpture, and as a special treat for those with a passion for both, “Essence: The Horses of Deborah Butterfield” is open at Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park through April 29, 2012. Eleven sculptures from four decades of her career have been arranged for this exhibition, allowing visitors to experience the full range of Butterfield’s work.

This display from internationally respected artist and lifelong horsewoman Deborah Butterfield is shared as a special exhibition in Grand Rapids, but her work is exhibited widely. Many of her pieces reside in museums, sculpture parks and private collections, so you may find one near you.

Exploring the horse as a form for a greater artistic and social statement, Butterfield’s horses evoke calm and wonder as visitors take in the sculptures. “Essence: The Horses of Deborah Butterfield” embodies her repertoire as a lover of horses and an artist of the highest caliber.

A Lifelong Horsewoman

Butterfield’s art conveys a deep respect, understanding and love of horses. She has said being born on the day of the 75th Kentucky Derby when a horse named Ponder won had something to do with her choice of subject matter. She admits to being obsessed with horses, but she asks what could possibly be wrong with that.

.jpg)

Deborah Butterfield in her Montana studio. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“The first thing that I saw in my life that I remembered looking important and wonderful was a horse. I was just moved by them in a non-rational, passionate way before I even had words to describe it,” said Butterfield in the video accompanying the exhibition.

While she was attending the University of California, Davis, she wrestled with a career choice. She knew she wanted to become either a veterinarian or an artist. Art clearly won, and she earned both a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Master of Fine Arts there. Butterfield’s primary art subject has remained horses since that time.

Butterfield began riding as a child and bought her first horse while she was still in college. Her preferred seat is dressage, and she rides at Prix St. Georges level.

She explained her connection to equines in the exhibition’s video: “I think the fact that I ride three horses most days, and groom them and wrap their legs and really take care of them, that I am fresh with the work, because every day you’re greeted with these magnificent, wonderful creatures. And every day they are different. They are in a different mood. And so that freshness, and the growth in them is what keeps me alive about it.”

Butterfield works out of two locations — her ranch in Bozeman, Montana, and a studio in Hawaii. She married fellow artist John E. Buck in 1974, and they have two sons. Butterfield taught sculpture at Montana State University. She values non-Western art such as Asian, African, Native American and folk.

A Broader Look at a Permanent Artist

I followed chief curator Joseph Becherer around the gallery as he explained the new exhibition to volunteers. Two of Butterfield’s horses are always on display at Meijer Gardens, so this exhibition is a broader way to experience an artist in their permanent collection.

“It’s a moment to experience this artist, this individual, in greater depth,” said Becherer.

Butterfield’s work has been part of Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park since nearly the beginning. The 30-acre sculpture park was created in 1995 when philanthropist Frederik Meijer donated his sculpture collection, and it claims to be the most popular tourist destination in West Michigan.

Two of Butterfield’s sculptures are on permanent display, so you can experience her work there even after the exhibition is over. Butterfield’s Cabin Creek was placed in 1999. Located near Nina Akamu’s The American Horse, a 24-foot tall bronze horse inspired in part by Leonardo da Vinci, Cabin Creek bridges visitors from a highly recognizable sculpture to the more abstract forms deeper in the park. They are each bronze horses but with a very different look and aspect.

Deborah Butterfield. "Cabin Creek," 1999.

Residing in a prairie-like setting of tall grasses, Cabin Creek stands as a horse in the wind. Appearing as though it is made of perishable and delicate driftwood, visitors often gasp when the tour leader tells them that it is indeed made of impermeable bronze.

Also on permanent display inside, in the common area, Small Dry Fork Horse is an example of Butterfield’s rare early horses. She crafted it in 1978 from sticks, mud, grass, steel and wire.

Deborah Butterfield. "South Dry Fork Horse," 1978.

Butterfield asked that her sculptures not be placed on platforms. This creates the organic feeling that you are in the field with the horses, and you may expect them to nicker to each other at any time.

“She wanted everything right on the floor. She wanted no barricades, immediate access,” said Becherer.

The exhibition is her first major Midwest showing in recent years. It contains her latest work of art, a greater than life-size piece just completed in December. Visitors can compare how many aspects of her work have changed and how many have stayed the same.

The Horse as a Wider Social Statement

The horse has always been a common subject of Western art, but Butterfield changed the conversation. She chose to make a wider political and gender statement with her work, departing from war art and creating equine art.

“What appears first to be about horses becomes about a pretty complex individual,” Becherer said.

Butterfield has expressed a dislike of war horses. Born in 1949, she developed as a person and as an artist during the Vietnam War, a significant and formative experience for her generation. She has explained that men and war haven’t gotten us far, so she wanted to explore equine art in a different vein.

Butterfield’s work also contains a subtle statement about gender. Gender roles were changing as she came of age, and she was one of two women in her master’s program. Women had been trying to shatter the glass ceiling in art, Becherer explained, since the 1950s, and Butterfield joined in that trend for gender equality. She became a significant figure and a bridge from the past to the future in the art world.

When Butterfield began sculpting horses in the 1970s, she was criticized for her choice of subject matter. No one was making art about horses any longer, and representation was supposed to come through a pop art style, according to common sentiment at the time. An artist returning to the recognizable was unexpected and not well received.

However, her career took off in the early 1980s as she “combined her love for the creature with her passion for art,” Becherer said.

Butterfield has explained that she is every horse she creates, that each one is a self-portrait. Each horse has a personality and an essence, and they reveal a sensitive view of the world. They are not all mares, she says, but many of them are. She names each horse, but her explanations are minimal and she prefers to keep the focus on the work itself. Her work is disarming, and that is purposeful.

“There is a degree of approachability in subject matter,” Becherer said.

Her prone horses, she has explained, are symbols of how comfortable she feels. Horses are animals of prey, so they can sleep standing up, enabling them to run away quickly if they need to. When they feel comfortable, they love lying on the warm ground for a nap. She decided to make prone horses after some harsh reviews of her work, just to show how much she doesn’t care about the wolves.

Materials, Construction and Scale

Butterfield’s choice of materials is significant, Becherer explained. She is an environmentalist, and she began sculpting horses in the 1970s using earth materials such as wood, mud, sticks and branches. Later, she moved to items “scavenged from modern industrial society,” he said.

She experimented with new materials, participating in what the larger art world was doing at the time. These later pieces have an “industrial roughness,” Becherer said.

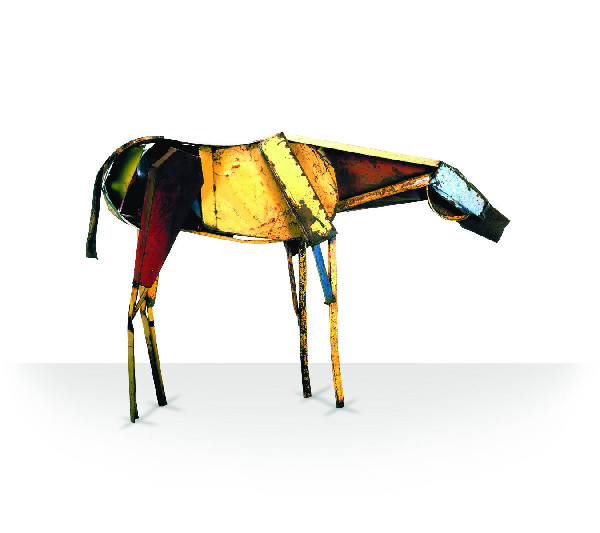

Butterfield constructed Billings, 1996, from a destroyed loading dock she found in Billings, Montana. She finds metal everywhere, basing her work on an instinct for gathering and scavenging.

Deborah Butterfield. "Billings," 1996. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Butterfield’s sculpture technique involves a “very traditional process,” said Becherer, and it transforms the media she uses. She manipulates the materials for her found metal pieces, completing the head and neck last as the form manifests.

She describes the construction process as a lot of fun. She compares it to building a fort as child from whatever resources are at hand, as just an urge to build things that some people have. As she builds, the personality of the horse emerges.

Pieces in the style of Cabin Creek are constructed first with wood that is wired together. Gantries, which look like swing sets with chains, support the piece. Then, each piece is numbered, molded and cast individually, translating them into bronze. Then the bronze pieces are welded together to form the individual horse. Butterfield uses a patina process to make the bronze appear like driftwood.

Butterfield has worked in multiple scales of horse size. Smaller pieces, such as Small Dry Fork Horse, are considered to be tabletop scale. Her most recent works are slightly larger than life-size, and the largest weighs 2,400 pounds. Her scale decisions, Becherer explained, were decided for practical purposes such as the amount of material she had to work with and commercial viability. Most of the large pieces are one of a kind, but some of the smaller works are an edition of three or four.

A Sophistication of Form

Representation of animals is once again in vogue, but Butterfield is one of the artists who pioneered it. Her work shows maturity in thinking about the form, understanding the creature, and knowing what materials to manipulate and change. She brings these two worlds — the creature and the knowledge of the materials — together with greater refinement.

Butterfield’s works are not portraits or likenesses, but they are based on individual horses. Dramatic, not static, they evoke the horse not only physically but inside also on the inside, portraying the essence of the creature.

Deborah Butterfield. "Palma," 1990. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Becherer explained that there is a sophistication in how Butterfield conveys “a certain level of pathos” in each piece. Her decision of how to twist the horse’s head into the room, how it affects the space, is evidence of masterful skill.

Her experience as a horsewoman comes across in the physical awareness of the creature. She understands how a horse’s neck moves and how a leg stands. The main aspects of her sculptures come across through the difference in contours, the conversation between contour and volume, and how the mass is described in each piece.

The volume and mass pull you into the piece, Becherer said, “And they stop being horses and become essays in abstraction. It’s like you enter into another room. You lose yourself in it, and it becomes an important visual experience.”

Whether you simply appreciate the horse or if you want to delve into the deeper artistic, social and historical elements of art, “Essence: The Horses of Deborah Butterfield” is a powerful and positive exhibition that is well worth the journey.

How you can go: Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park, located in Grand Rapids, Michigan, is open 362 days a year - Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday 9 am-5 pm, Tuesday 9 am-9 pm and Sunday from 11 am-5 pm. (888) 957-1580

Exhibition dates: January 27, 2012 - April 29, 2012

Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park has paired several equine-related events with the exhibit. Find out more on the exhibition’s website.

Karen Braschayko is a freelance writer and horse lover who lives in Michigan.