The North Carolina Shackleford Banks Horses: A History of Tribulations with a Few Surprise Endings

Hurricane Hits the North Carolina Coast and Two Shackleford Pony Foals Live to Tell the Tale

by Claire Caldwell

Recently, people living along the East Coast of the United States prepared themselves for the arrival of Hurricane Irene, rumored to be the most potentially devastating hurricane the northeastern Atlantic coastline had seen in decades. The category three storm hit land along the Eastern Coast of North Carolina’s Outer Banks: home to the wild Shackleford horses. In the midst of a raging hurricane, these horses resiliently defied the destruction of the storm; but their story of survival has a much more extensive history.

One of the Shackleford Banks' horses, named Merlin

courtesy of the Foundation for Shackleford Horses

The Historical Transatlantic Journey of Shackleford Horses from Spain

The Shackleford horses arrived to the East Coast in the early 16th century having traveled across the Atlantic from Spain with some of the original Spanish colonial explorers. They waded ashore the Outer Banks and were then captured and brought inland. Thereafter, Shackleford horses became integral to the colonial way of life, broken and used as riding and plow horses in crop fields.

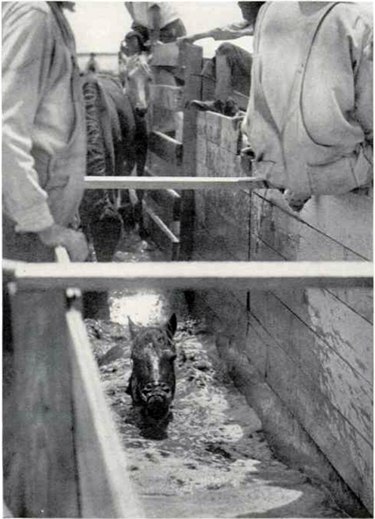

Shackleford ponies are steered through a chemical mixture employed to cure them of ticks, circa May 1926 National Geographic, photograph by Clifton Adams

National Geographic reported on this ancient lineage of horses in the 1920s, at which time there existed between 5,000 and 6,000. A century later, there are fewer than 320 of this Spanish breed. In the mid- to late-1900s the National Forestry Association advocated for the removal of the horses from the North Carolina coastline as a measure to reduce beach erosion.

A herd of the wild Shackleford horses being corralled of the North Carolina coast, May 1926 National Geographic, photograph by Clifton Adams

At the time, the horses were isolated in three locations: the Shackleford Banks (so named in the 1700s), Ocracoke Island in Cape Hatteras National Seashore, and Corolla beach. By the grace of local samaritans in these three beach communities, the wild horses were able to persevere in the area. On Ocracoke Island a boy scout group took on the adoption of the horses as a project. They trained and learned to ride and care for the horses, becoming known around town for escorting the then Governor Hodges to public events.

The horses on Shackleford Banks, the largest and most genetically viable herd, were defended by a man from Harker’s Island. He begged the state legislature, of his own volition, to leave the horses undisturbed, insisting that they’d been there for centuries and posed no threat to the local habitat. In 1997 the Shackleford Banks Wild Horses Protection Act was passed, ensuring that a herd of Shackleford horses be protected on the Outer Banks. The law stipulates that a minimum of 110 horses and a maximum of 130 is maintained on the Shackleford Banks. Under this federal law, the National Park Service at Cape Lookout National Seashore and the Foundation for Shackleford Horses co-manage the horses on the islands. In the instance of a population approaching the maximum cap, a select number of mares are injected with a birth control and young horses of the largest family lineages are removed from the island.

Mother and foal graze on the dunes of Shackleford Banks

On the 10th of June, 2010 the Outer Banks Wild Horses were named North Carolina’s state horse.

One of the wild coastal horses takes a wade in the calm inlet waters

Hurricane Irene Delivers Miracles Amidst Damage

Today the horses live peacefully and undisturbed on Shackleford, Ocracoke (managed by the National Park Service, Cape Hatteras National Seashore), and Corolla beaches (overseen by the Corolla Wild Horse Fund). Employees of the National Park Service and volunteers of the Foundation for Shackleford Horses are charged with protecting and maintaining the horses on the Shackleford Banks, and will enter the wild horses' habitat to observe but do not interfere with their natural way of life. These organizations play a particularly vital role in locating all of the Shackleford horses when hurricanes, such as Irene, whip through the region.

A young ponies with similar facial markings

After a major storm, it is essential to get a “head count,” so to speak, of the horses to ascertain that they are in good health and have not been hurt or killed during the hurricane. The employees charged with assessing the damage to the herd are able to account for the horses by simple facial marking recognition. During Hurricane Irene, to the dismay and glee of the volunteers and National Park Service employees, in lieu of injured horses, two foals were born!

Mother sits alongside her newborn foal

Dr. Rubenstein's System of Naming

Year 2011 the theme for naming the Shackleford horses is “Spanish names;” and the method for assigning names is more complex than one would imagine. Dr. Daniel Rubenstein, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton University, developed a system for naming these horses which dictates that the foal’s name start with the first letter of its mother’s name. This methodical approach allows for an improvised means of tracking lineage. Of course, all of the horses still residing on the Shackleford Banks and elsewhere along the North Carolina coast have been blood typed and DNA tested to confirm their Spanish origins. These official records do exist; the name heritage is simply meant to facilitate current day-to-day observations of the horses.

The two resilient foals who withstood a natural disaster also proved stubbornly difficult to name. The first was born of a mare named Anastasia. The Foundation and Park Service wanted to name the foal in keeping with the hurricane theme, but they could not pinpoint a word in the Spanish language, beginning with the letter ‘A’ that kept with this idea. Thus, they strayed from the yearly motif for naming and decided upon Aftermath.

The second foal was descendent of a mare named Wallace—clearly mistaken in her own birth by a novice hippologist for being a boy. As it turns out, there are no words in the Spanish language beginning with the letter ‘W;’ the Foundation for Shackleford Horses volunteers were stumped. After a bit of brainstorming though, they arrived at a name. The people of one of the Wichita Native American tribes, when initially encountered by French explorer Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe, were referred to by the Spanish word Houecha. Now this tribe is called the Waco tribe. Given there are no authentic Spanish names beginning with ‘W,’ this word (an English translation, in essence, of the word Houecha) was the closest relative the staff could settle upon.

Thus, Waco and Aftermath, born in the eye hurricane, became the two newest additions to the Shackleford Banks’ herd. When speaking with locals and asking why the horses occupy such a soft spot in their hearts, history and culture, they inevitably answer, “these islands have been around for centuries. People used to inhabit the Outer Banks as well, but over time they were driven away by the harsh and unpreventable weather conditions. The horses have remained though. More than anything, we respect them for their resiliency.”

Shackleford Banks pony named Spirit

About the Author: Claire Caldwell is a freelance journalist, pursuing a Bachelor's Degree in English Literature and French language at American University in Washington, DC. She is an avid world traveler, having lived in the United States as well as Europe she has also spent time in the Caribbean and Northern Africa. While living in Paris, France, Claire blogged about the differences between linguistic and cultural traditions between America and France, as well as about hot-spots and tips for traveling to the City of Lights. She has also worked for the women's travel site, Pink Pangea, blogging about safe ways for women to travel the world independently. She is currently pursuing creative ventures while finishing her degrees.